On May 8, 2024, President Ferdinand Marcos Jr. formed the Special Committee on Human Rights Coordination under Administrative Order No. 22 (AO22) to “enhance the mechanisms for the promotion and protection of human rights in the Philippines.” This so-called “super body” is also intended to “sustain and enhance the accomplishments of the United Nations Joint Programme on Human Rights (UNJP), […] through institutionalization of a robust multi-stakeholder process.” The UNJP is a three-year technical cooperation between the UN and the Philippine government, which expires on July 31, 2024. Existing mechanisms similar to the AO35, which was supposed to detect political assassinations, had so far proven to be inadequate.

The committee’s secretary is with the Presidential Human Rights Committee (PHRC) and is headed by Executive Secretary Lucas Bersamin as Chairman and Justice Minister Crispin Remulla as Co-Chairman, with support from the heads of the Department of Foreign Affairs (DFA) and the Department of Interior and Local Government (DILG).

The AO22 has caused uncertainty and concerns among local human rights organizations. According to Karapatan, this “unnecessary layer of bureaucracy,” as Amnesty International called the new mechanism, is a “tactic to evade accountability” for human rights violations. According to civil society organizations, the UNJP was unavle to achieve its aim to hold perpetrators of serious human rights violations accountable in the context of the so-called “war on drugs.” “Why continue something that has already failed”, asked Carlos Conde of Human Rights Watch (HRW) in an interview with Rappler on May 14, 2024. To date, there has been no independent investigation of the UNJP. A civil society demand to extend the UNJP on the basis of a strengthened format received no support from the Philippine government.

The new committee includes neither the engagement of civil society groups nor the Commission on Human Rights (CHR), which played central roles in the UNJP. For Conde, it is therefore also questionable why civil society groups were not even consulted by the government for the composition of the new committee. In a statement, the CHR, however, welcomed the AO22 “as a step in the right direction.” According to Conde, the CHR, as an independent institution with a mandate to investigate human rights violations since 1987, would be in the “best position” to take on the tasks of the new committee.

It is also worrying that the members of the AO22 are members of the controversial Anti-Terrorism Council (ATC), which has already declared numerous human rights defenders to be alleged terrorists. In addition, the new committee’s ability to invite other government agencies, such as the ATC or the controversial National Task Force to End Local Communist Armed Conflict (NTF-ELCAC), as an “observer” is concerning. The NTF-ELCAC is known for “red-tagging” (i.e., branding individuals or organisations as “terrorist”) human rights activists.

Conde also criticized that the AO22 was more of a “political move” to keep up the appearance that the government was serious about improving the human rights situation. If the government really wanted to do so, Conde explained, it would be willing to cooperate with the International Criminal Court (ICC) in its investigation into alleged crimes against humanity in the context of the so-called “war on drugs.”

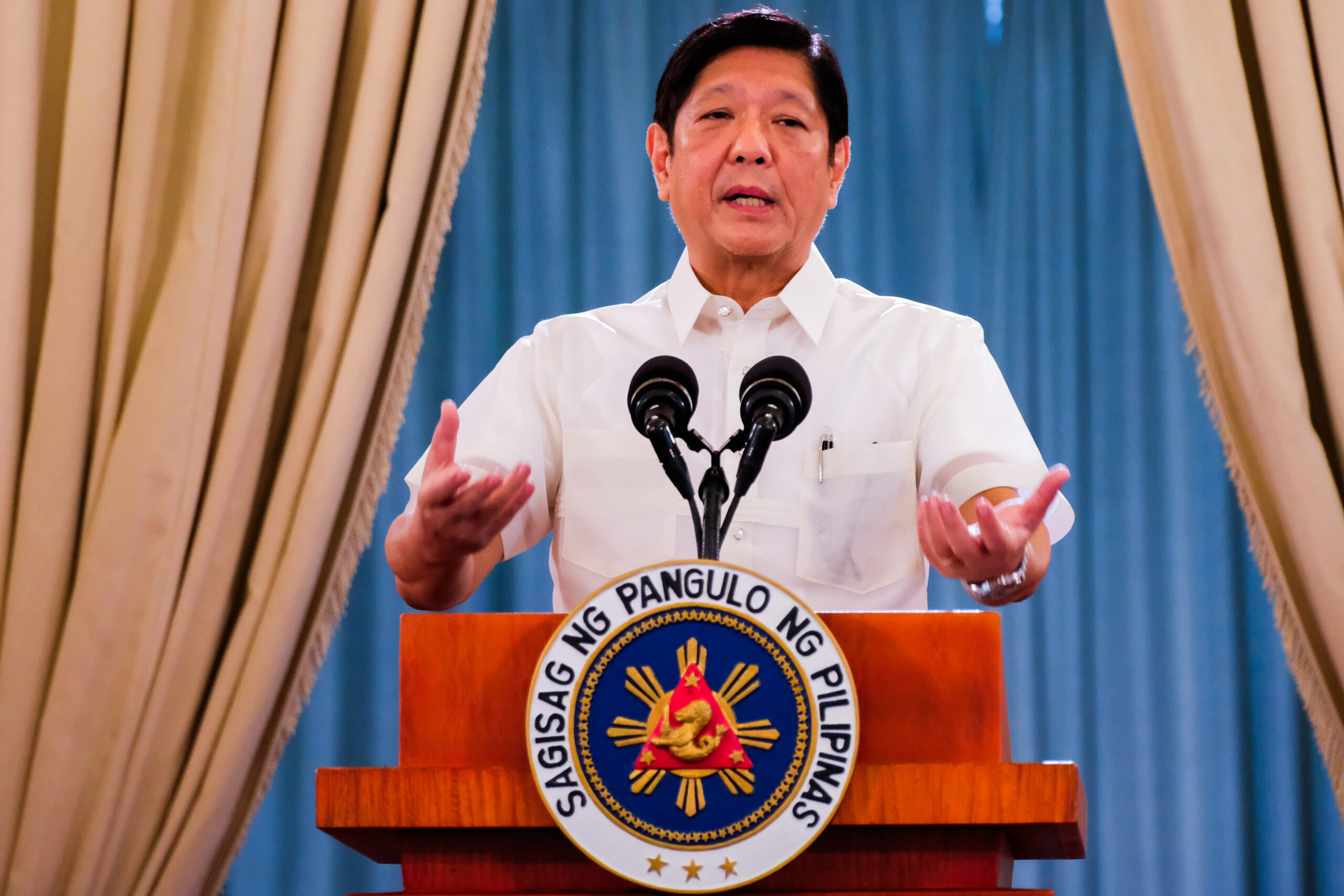

Photo © AMP