Nearly a year after Cora Jazmines filed petitions for writs of amparo and habeas data* over the disappearance of her husband, labor activist James Jazmines, the Court of Appeals finally held its first summary hearing on October 2, 2025.

James Jazmines was disappeared on August 23, 2024, after attending a friend’s birthday celebration. That friend, Felix Salaveria Jr., was disappeared five days later; both remain missing. James, a veteran labor and student activist, had worked with the League of Filipino Students, Kilusang Mayo Uno, and the Amado V. Hernandez Resource Center. His wife Cora, under temporary court protection, continues to seek accountability from several military and police officials, including former AFP chief Romeo Brawner Jr. and former PNP chief Rommel Marbil. “Red-tagging” is a practice of labeling individuals or organizations —often without evidence — as members of the armed communist insurgency or as terrorists, which can expose them to harassment, violence, or legal repercussions.

JL Burgos, chairperson of Desaparecidos – an organization of families and friends of victims of enforced disappearances – said they remain cautiously optimistic about a favorable ruling to the petition for protective writs filed by Jazmines’ family.

In a statement, Burgos expressed uncertainty about the outcome, noting the Court of Appeals’ inconsistent record in granting such writs. He also cited the court’s previous denial of writs for environmental activists, disappearance survivors Jhed Tamano, Jonila Castro, and Francisco “Eco” Dangla III.

Despite the court’s acknowledgment that Dangla was abducted, a victim of so-called “red-tagging,” and that security forces failed in their duty of diligence, his plea for protection was still denied, underscoring the gap between state accountability and justice.

Dangla, assisted by the National Union of Peoples’ Lawyers (NUPL), filed a motion for reconsideration, presenting evidence linking military personnel to his abduction.

Human rights group Karapatan criticized the ruling as reinforcing impunity, saying it “admits the crime but absolves the perpetrators.” Similar denials have been issued in the cases of the enforced disappearance of Jonila Castro and Jhed Tamano as well as killed human rights defender Zara Alvarez.

The controversy has revived calls for the Philippines to ratify the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons Against Enforced Disappearance (ICPPED).

Human rights groups argue that the country’s 2012 national Anti-Enforced Disappearance Law has failed, with zero convictions, no budget for implementation, and persistent noncompliance by security forces. Ratification of the ICPPED, they say, would allow international oversight and strengthen accountability.

The killings of environmental defenders Rudolph Dela Cruz Espe and Rico Gonzaga Malubay in Davao Oriental on July 26, 2025, just days before President Ferdinand Marcos Jr.’s State of the Nation Address, highlight the risks faced by land and environmental defenders.

According to Global Witness, the Philippines remained the deadliest country in Asia for environmental defenders in 2024, marking its 12th consecutive year at the top of the list.

* The writ of amparo is a legal remedy and protection available to any person whose right to life, liberty, or security has been violated or is threatened. The writ of habeas data protects a person’s right to privacy arising from unlawful collection, storage, or use of a victim’s personal data.

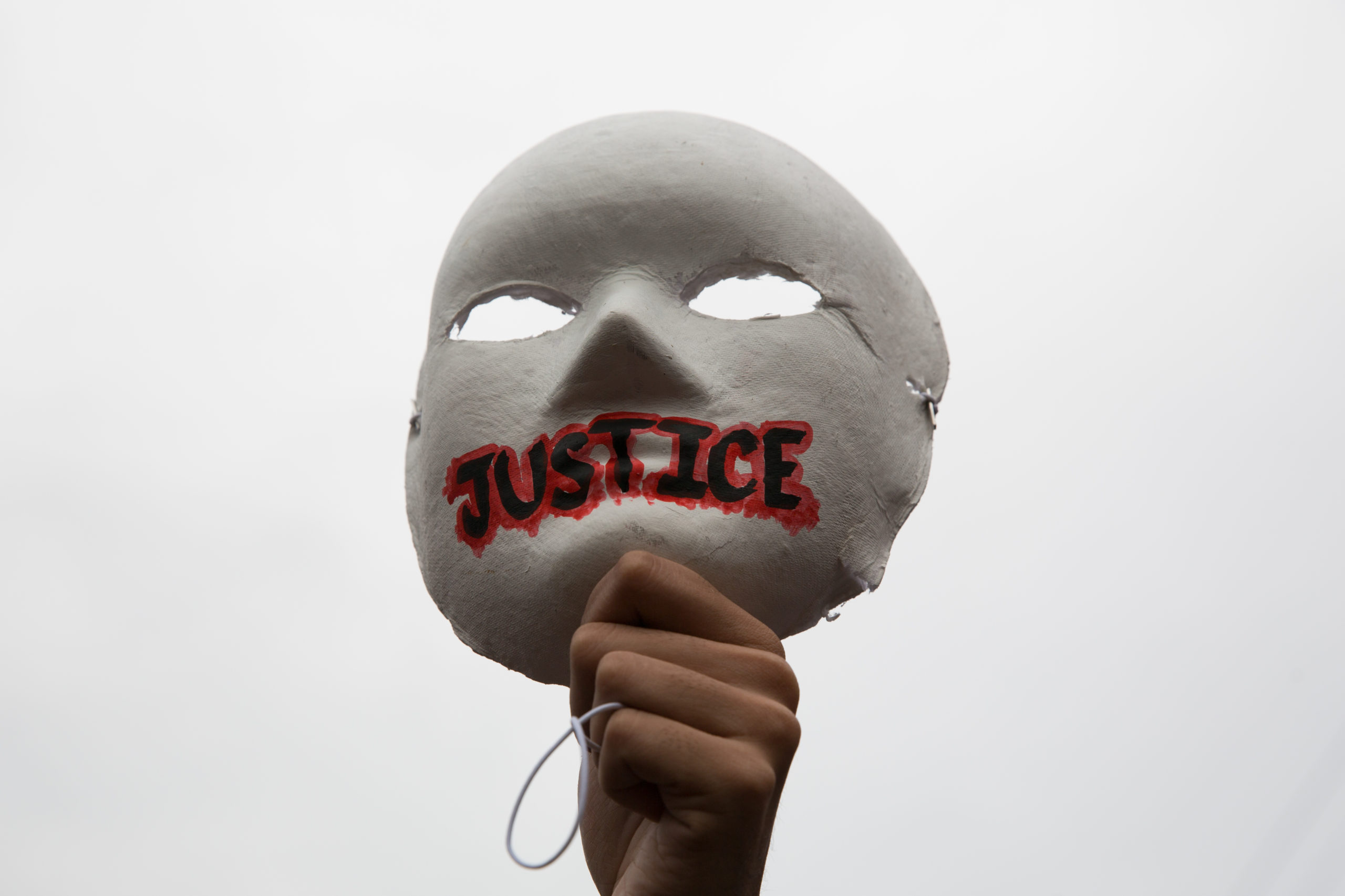

Photo © Raffy Lerma